As part of my research in the project „P/Reenacting Emotions. Feeling Futures in the Performing Arts,“ I had the opportunity to attend the entire program of the 19th edition of the TransAmériques Festival. The following text provides insight into my experiences on site in the form of a festival report.

A human body and the garbage surrounding it is made invisible as it is swept under a large white plastic sheet lying in the corner of the stage. Deep breaths. An ear-piercing fire alarm warns that the stage is overheating, only to be switched off again and again to keep the performance going. Deep breaths. An ensemble of young black ballet dancers defy the exclusion of their bodies from classical dance repertoires, using their pointe shoes as percussion instruments and liberating themselves from the violence of holding on to traditions that are not theirs. Deep breaths. These are three examples of strong scenic moments from the 20 productions shown at the 19th Festival TransAmériques (FTA) from May 22 to June 5, 2025 in the French-Canadian city known by its colonial name, Montréal. They also gesture towards an uncompromising approach to the contemporary complexity of global interdependencies that characterized the festival program.

This is the fourth festival under the joint leadership of directors Martine Dennewald and Jessie Mill. In many ways, FTA 2025 upholds traditions established by Canada’s largest international theater and dance festival, founded in 1985. At the same time, Dennewald and Mill are forging institutional change: The evolution is reflected in the festival’s programming, with its commitment to new audiences and environmentally sustainable practices, as well as thoughtful efforts to create formats that support encounters and discussions among people whose paths would be unlikely to cross in everyday life.

The process of decolonial transformation also includes recognizing the unlawful seizure of land and the cultural genocide of the First Nation people living on the Tio’tia:ke and Mooniyang territories – specifically, in the case of Montréal, the Mohawk and Anishinaabe. This acknowledgement gestures towards the colonization of all indigenous peoples, whose stories, languages and cultural practices must be tangible presences at a festival dedicated to trans-American lifeworlds.

Violence, Then and Now

This decolonial perspective informs a key curatorial focus that emerged throughout the festival: an unflinching confrontation with genocidal violence and its legacies on the traumatized bodies of subsequent generations. Within the context of recent events in Gaza, this focus can also be understood as an act of solidarity with the civilian population.

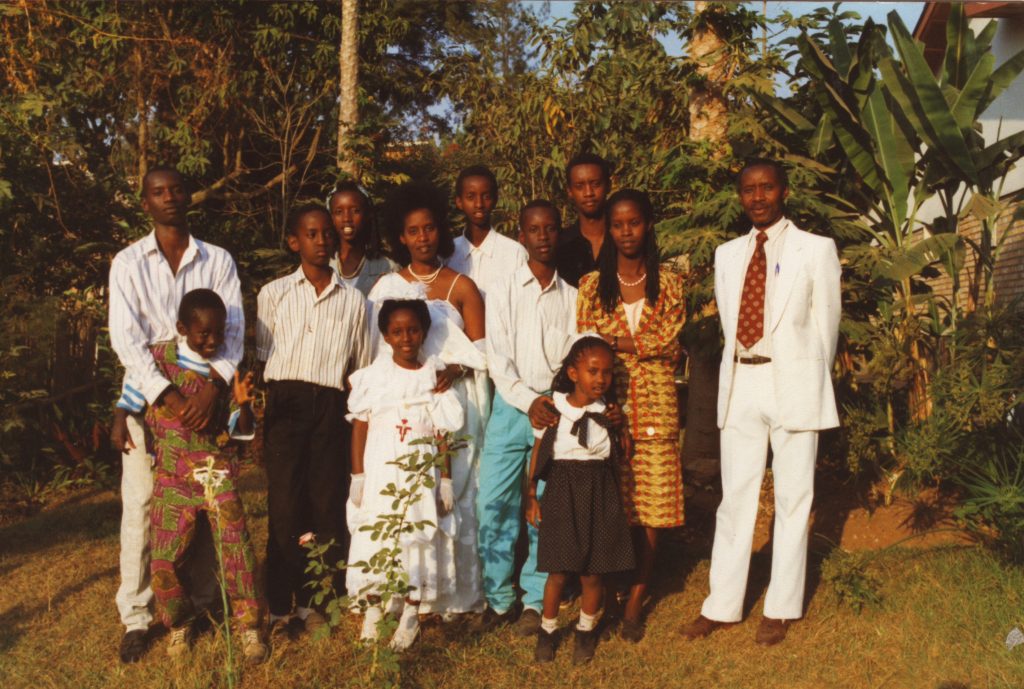

The musical lecture performance “Hewa Rwanda” by Dorcy Rugamba and the short film “Ibuka, Justice” by Justice Rutikara examine the genocide committed against the Tutsi in Rwanda in 1994. Both artists lived through their own unique and yet shared “end of the world”: Rugamba, as an adolescent, and Rutikara, as a child, each lost large parts of their families and were socialized as part of the African diaspora in Europe. Their respective artistic practices are dedicated to resistance against the act of forgetting.

The same resistance drives the work of Rwandan-born musician and choreographer Dorothée Munyaneza. Her dance performance “Toi, Moi, Tituba…” is based on the novel “Moi, Tituba, sorcière…” by Maryse Condé: a fictional biography of Tituba, a woman who was enslaved by a British Puritan and persecuted in the Salem witch trials. Munyaneza explores the epistemic violence inflicted on Black women like Tituba, including the absence of their voices in the archives. In an interplay of dance, memory, song, Munyaneza’s mothertongue Kinyarwanda, neon lights in the otherwise dark stage area, and a complex soundscape (created in collaboration with Khyam Allami), she traces this collective absence in connection with her own identity and her female ancestors. Elements of the work draw from aesthetic systems of reference that I have no framework of understanding for. The choreography is defiant and decolonial, insofar as it resists the narrative of supposedly universal art forms and experiences, as well as any strategic self-exoticization to indulge a performing arts industry that is still predominantly white.

Theater Today – To What End?

The dangers of self-exoticization and emotional exploitation are also explicitly problematized by performer Tiziano Cruz in his solo work “Wayqeycuna” (engl. „fork in the road”). The piece opens with the artist’s utterance, “You can consume me now,” followed by a depiction of structural poverty in northern Argentina via large-format images of people from his home region, Jujuy. The real, the fictional, and the fantastical merge as he tells of his sister’s death while introducing us to indigenous cosmologies that do not separate these planes as neatly as non-indigenous perspectives tend to.

With Cruz, artistic creation takes on an existential dimension: On the one hand, it offers him a concrete escape from poverty; on the other, he shoulders the painful responsibility of sharing his lifeworld with people on other continents, in places like Canada, a country whose companies are heavily involved in neo-colonial and extractivist lithium mining and the associated destruction of his homeland. Instead of moral indictment, however, Cruz chooses an act of immense generosity, as he opens up the stage to hold a ritual of remembrance. Small loaves of bread, baked with guests earlier, are now eaten together to the sound of music and song. One answer to the question “why theater now?” might be the possibility of reflecting and enacting community work as an antidote to widespread social isolation.

“Making theater in this world – to what end?” is the question underpinning “Centroamerica,” a piece by Luisa Pardo and Lázaro G. Rodríguez from the Lagartijas Tiradas al Sol collective as well. As part of their research trip through neighboring South American countries, they met Maria from Nicaragua, who had to flee her home country after joining the peaceful “Madres de Abril” protests against the authoritarian Ortega regime. Ever since, she believed it would be impossible to transfer the body of her brother, who had died of COVID, from an anonymous mass grave to the grave site of their grandmother. In this documentary-style theater piece, Pardo and Rodriguez recount how they used (acting) performance to travel to Nicaragua in Maria’s stead to facilitate the grave transfer for her.

By inviting artists from Mexico, the indigenous north of Argentina, as well as amplifying the voices of (afro-)diasporic artists in dance and theater, Jessie Mill and Martine Dennewald are putting perspectives on stage that were previously underrepresented at FTA. This second curatorial focus marks a palpable shift away from the festival’s historical Eurocentrism and towards a more diverse future of multi-perspective artistic worldviews. This includes inviting “Hatched Ensemble” by Mamela Nyamza (which toured successfully in Germany), “Lacrima” by Caroline Guiela Nguyen for the festival opening, and the secret audience favorite “Shiraz” by Armin Hokmi – which are also among my personal highlights of 2025 so far.

Space for Grief Work

A third curatorial focus, one that connects the international and national productions, is the theme of grief. Notably, the theme of losing family members was present in all productions highlighted so far, and it also permeates the Canadian productions “Heaven FM” by Natalie Tin Yin Gan from Vancouver, “Concerto” by Charlie Khalil Prince and Olivia Tapiero, and “Un-Nevering” by Thea Patterson from Montréal. In these works, the artists use the space of their respective practices as a means of experience grief work as something more communal. They imagine and enact alternative approaches that make adequate time and space for the active, bodily processing of emotions – a stark contrast to the ways in which grief work has been made invisible and increasingly individualized in the Global North.

In terms of craftsmanship, “Concerto” stands out as a mixture of experimental music and dance theater. Prince and Tapiero create an inhospitable stage scene of scattered garbage, plastic sheets, cables and the remains of a protest camp. Alongside this installation, the audience are presented with a video montage of accelerated images of atrocities, suffering, and climate catastrophes almost impossible to process. The artists juxtapose these elements with a radical aesthetic of deceleration, centered on small, more introspective movements and the controlled assembly of materials against a backdrop of looped sounds. “Concerto” represents an attempt – small-scale as it may be – to affirm one’s own power to act as fuel to carry on.

It is worth pointing out that none of the three works prescribe a particular emotional response or predetermined code for the audience. Instead, they allow us space and time to collectively calm our senses and lean into subjective feelings, which are so often brushed aside in our hectic day-to-day. I cannot recall ever having been surrounded by so many crying people in the audience on so many consecutive nights. Perhaps that is why the call to “Respire!” (engl. „deep breaths!“) from “Lacrima“ became something of a refrain echoed in post-performance conversations.

The Festival as Caring Institution

Attending the festival in its entirety brought home its immense importance for the Canadian theater and dance scene. As a beacon institution realized largely through public funding, it is an invaluable co-production partner for local artists, and it is able to bring major international productions to Canada as aesthetic inspiration, even in times of financial cutbacks to the arts. FTA involves school children and students in its various activities, and its contributions to community and the world are more than symbolic. For example, the festival regularly hosts a “Decolonial Ecology Day,” an event that centers indigenous forms of knowledge, and participates in climate neutrality initiatives, such as the Ecodesign Guide featured as part of FTA 2025. It is evident that FTA is an ecosystem of lived values rather than an institution dutifully ticking off boxes: an organization committed to reflecting what is negotiated on stage at the institutional level.

The festival is carried by a strong backbone of curatorial choices: “Terrains de Jeu”, the framework program curated by Jessie Mill and Florence Bisson that takes place at the thoughtfully designed festival center; the many networking opportunities; the additional “presenter showings” in the mornings, where I had the opportunity to experience two highly impressive choreographic works by Catherine Gaudet and Lara Kramer, respectively; and, finally, the decision to perform the high-profile dance production “C la Vie” twice on the open air stage of the Théâtre de Verdure in La Fontaine Park, for the general public and free of charge. The audience’s excited response to the sophisticated contemporary dance piece from Burkina Faso is something that will stay with me for a long time.

Overall, the impressions I gathered at FTA confirmed my hypothesis that dance is the medium of the moment when it comes to the production of aesthetically striking works. I suspect that this is due to the ever-broader spectrum of new and emerging fusion techniques of different dance styles, as much as to the growing artistic-choreographic research on the body and trauma, which explores sensations as literal movement material beyond language.

Despite engaging head-on with the injustices, atrocities and horrors of the world, as the festival was drawing to a close what lingered was a sense of admiration, and of gratitude, for the moments of palpable solidarity between people from Canada and the sixteen other countries: countries from which people traveled to Canada despite increasingly adverse visa requirements; people who had previously known very little about each other but who discovered similarities in their stories, struggles, and pain at the festival. Deep breaths.

This festival report was first published in German on nachtkritik.de. The English translation is by Jos Porath. Thanks to Martine Dennewald for her excellent hospitality; and also to all the local discussion partners.