Earlier this year, Laibor Kalanga Moko and Maren Wirth visited the famous Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Founded in 1884 the institution houses collections from various parts of the world, most of which were appropriated during British colonialism. We first initiated contact with Laura van Broekhoven, the Director of the Museum, in 2021. At the time, Laibor had just shifted the focus of his research from the ethnographic objects collected by German colonial armies during the Maji Maji war between 1905 and 1907, which are housed at the Ethnological Museum in Berlin to the museum’s infamous Maasai collection. Having conducted some initial ethnographic research, both in person and remotely, he came to the shocking realization that what he had found in Germany was not only of inestimable importance to the Maasai, but also highly problematic.

As this was happening in Berlin, on the other side of the North Sea, a team from the Pitt Rivers Museum were beginning to intensify their collaborative efforts on their own Maasai collection. Samuel Nangiria, a young community leader, activist and presently the Director of the Ngorongoro NGO Network, had visited the Pitt Rivers Museum together with other indigenous leaders in 2017. The group visited the museum as part of an „Indigenous Leadership Training Program“ led by InsightShare, an UK based organization working with marginalized communities to address their concerns and advance their interests using participatory video making. Like Laibor, Samuel immediately identified many of the „objects“ in the collection as problematic and out of place in the space of the museum. He expressed his concerns to Laura, which led to the initiation of the project called „Maasai Living Cultures,“ which aimed to address some of the questions and answer to the demands raised by the presence of these „objects“ in the Pitt Rivers Museum.

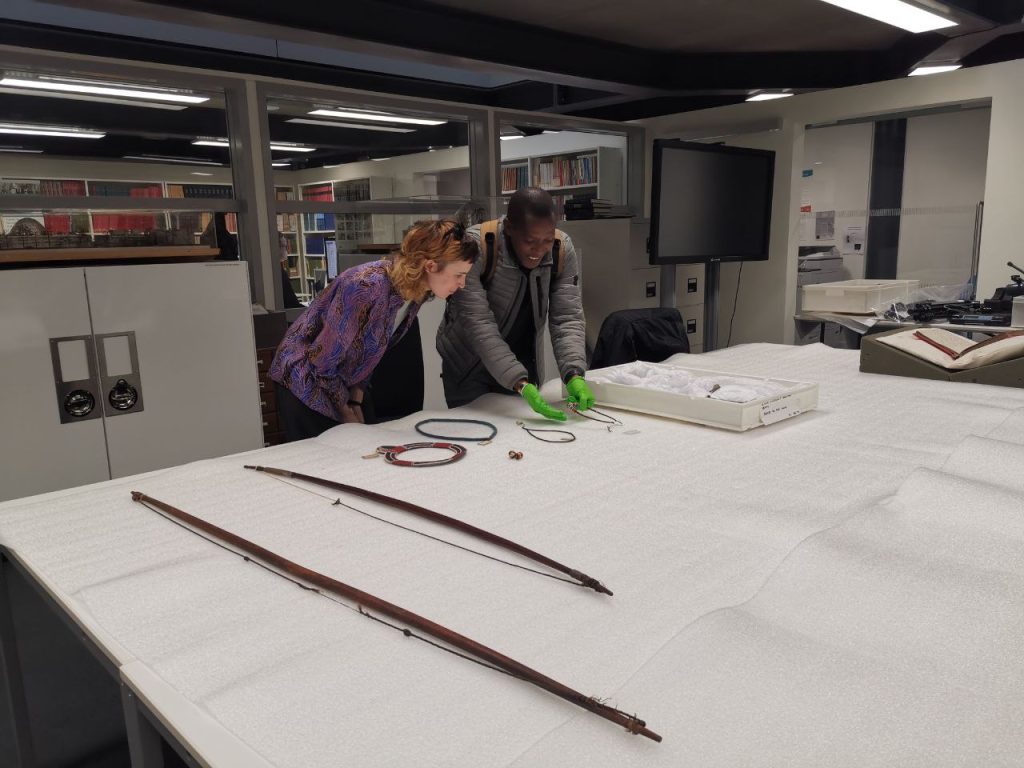

When we got the opportunity to exchange with Laura and her research team in 2021 via zoom, we were more than happy to learn from their experiences. During our brief conversation, we discovered overlaps between the reactions of Laibors‘ research partners, and the Maasai delegates who had previously visited the Pitt Rivers Museum. People were highly unsettled by their encounter with the objects, expressing shock, anger and disbelief. We discussed the types of Maasai objects found in both museums, the British and German collectors, and the possible contexts of acquisition. At that time, the collaborative team had already specified the five most sensitive objects from the collection; identified their families of origin with the help of a Maasai Laibon (spiritual specialist), and were in the process of evaluating adequate approaches to reconciliation with the communities from which these objects where taken. The conversation ended with Laura’s a warm invitation to visit the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford to view the collection and to exchange further with members of the team. However, because of Covid-19 restrictions, as well as our own research in Tanzania, we were only able to accept the invitation four years later.

We arrive on a warm spring afternoon. We are both new to Oxford, and the city seems to radiate the intellectual heritage of more than six hundred years of academic elites. We wander through the streets on our way to the hotel and wonder where people actually live, as all we can glimpse at through the windows of the small brick houses are bookshelves. Without any direction, we stroll around this place that sparks history and end up in front of the Pitt Rivers Museum by coincidence. The entry is free, but visitors are asked to make a small donation to visit the exhibitions. We enter the impressive neo-gothic, Victorian building through large wooden doors and find ourselves in the Museum of Natural History, which is located in front of the Pitt Rivers Museum. The sun of early spring scatters through the open glass roof illuminating the centerpiece of the exhibition — two enormous dinosaur skeletons. Just below the ceiling, floating, as if they were still swimming, hang the remains of five whales. Surrealistically a choir is singing on one side of the large hall, in between the remains of animals — some existing, others long extinct.

A sign leads us through a door in the back into another exhibition hall. This is how we enter the famous Pitt Rivers Museum. The first thing we notice is the sudden change of lightning. Unlike the atrium of the Museum for Natural History, the Pitt Rivers Museum does not have a glass ceiling. Artificial light comes from little spotlights around the circumference of the three open galleries. The second gallery stretches above us as we enter, trying to grasp the gloomy space. The main exhibition floor consists of square glass vitrines, dispersed around the hall. As we walk down the stairs, stepping into a narrow space that opens in front of us like a labyrinth, it feels like we are swallowed by a mass of objects. The glass showcases do not seem to stand in any particular order. We begin to walk between them, and soon lose sight of the entrance, and after a few minutes, of each other. We stroll around objects from around the world “collected” and gathered here using Western typological categorizations. The place seems noisy, even though it is already late, and we are practically the last visitors. We feel watched by the faces staring at us from the walls and the display cases, as we wander around aimlessly. Letting ourselves float on by like this, we finally meet each other in front of a showcase titled, “Human Form in Art,” in which we see Congolese Minkisi, ancient European images on wood and ivory, figures made from diverse materials, and various Masks from around the globe. Next to the objects, there are yellowed handwritten notes describing their place of origin, their meanings, and their functions. “Human form in art,“ Laibor says out loud. A voice coming through the speakers asks us to move towards the exit—the museum will close soon. As we leave the monumental building through the front gates, we both gasp for air. Even though Maren’s chest feels tight from the experience, we are glad we at least got to see the exhibition before our meeting the next morning.

As we walk back towards the city center, we try to process our impressions, especially reflecting on our discomfort with what has been termed “art” at the museum. The categorization of indigenous material culture as art contains a tacit, albeit outdated acknowledgment that people other than individuals from the Global North are capable of intentionally producing meaningful and beautiful things. However, our own research perspective, and that of other contemporary scholars working in the field, show that things categorized as art may not at all fit into this classification scheme. They may at the same time serve a spiritual purpose; may be used in everyday life; may serve as powerful presentations of craftsmanship, leadership and cultural belonging. A categorization of these diverse entities as “art” reveals a colonial attitude that signals an entitlement to collect, categorize, and claim ownership not only of the objects and cultural knowledge related to them, but also of the epistemological basis of humanity and the world in general. It evinces Western entitlement to universal truth.

The next day, as we meet Laura and her colleague Marina De Alarcón, the curator and joint head of collections, our conversation stands in stark contrast to what we felt the day before. The aims of the Maasai Living Cultures project, which places the emphasis on decolonizing approaches by acknowledging the coexistence of alternative knowledge systems seem at odds with the entire framework of the exhibition. The atmosphere, which reveals a new affective arrangement, supports the feeling that we are now in a differently-structured space. Laura invites us into her light flooded office; it is situated in the back of the museum and its floor-to-ceiling windows expose the unglamorous grey backyard of the museum. We sit at a long table and are offered coffee and cookies. Laura and Marina describe their experiences with their collaborative project, colorfully painting an image of their shared journey from its beginning in 2017.

It feels to us like this is not just any ordinary office project, but something truly personal. Their story is moving and emotionally rich. We are all aware of the significance of this collection, and the historical as well as ongoing violence attached to it. Maasai belongings are closely connected not only to their individual owners, but to entire communities; they continue to hold power and affect people’s lives long after they were taken. Since it is not possible to sell these belongings or to give them to anyone outside the family, it is apparent that they were taken by force. Their absence in the Maasai communities is causing miscarriages, infertility, disease, and even death. These belongings resist their alienation in the space of the museum, and their presence hovers over us like a shadow, demanding justice. Between our stark accounts, we are also able to laugh together, as Laura describes how she was herding cattle early one morning, as part of the necessary “healing” rituals with different families and communities in the villages. To redress the violence connected to the collections, Laura and her team travelled to Kenya and Tanzania in 2023 to perform Elata Oo Ngiro ceremonies. As part of the reconciliation rituals, each family was given 49 cows based on Maasai customary law.

As we continue to talk, it seems to us like Laura’s and Marina’s engagement is not merely intellectual, but also emotional and embodied. Their narration is characterized by them having been there, having smelled, and touched, and tasted, and danced with their bodies. It shifts the focus from categorization schemes and glass displays, towards something lived and relational. We discuss different aspects of responsibility and the role of the museum in broader societal crisis, such as climate change, which disproportionately affects those whose belongings are still in the museum’s possession. We talk about colonial legacies, the ways in which they continue to frame relations between the Global North and the Global South. We discuss pragmatic and practical approaches that could resolve such inequities, like collaborations that allow not only spiritual healing, but also comprehensive and meaningful transformation based on voices, needs and demands of communities from the Global South. We also talk about the political complexities that come with an engagement labeled as “woke culture,” as well as the political shifts towards the right in the Global North—developments that threaten already fragile newly-emerging alliances. As we finish our discussion, we realize that we exceeded our allotted meeting time by almost two hours.

The visit leaves us wondering; what might be the future of “the Museum” in general? The contrast between the official exhibition space, and the research done in its backrooms stand in such stark contrast, that the museum appears to collapse in on itself. We wonder how institutional change may be stimulated through such personal, individual engagements. Laura claims that their research has changed the museum, but we wonder how such change—based on personal interactions and sympathetic research experiences—carries across institutional structures and leads to transformations that exceeds individual actors, such as Laura and Marina. Can the affective forces that bind the Pitt-Rivers-Team and their Maasai collaboration partners overcome the racist and colonial forces of persistence of the institutions and societies that house them?

When we revisit the exhibition later in the afternoon, we notice that around certain display cases there are interpretive panels of various sizes. They range from small comments to a whole box covered up by information posters. This showcase, which is still labeled „Treatment of Dead Enemies,“ until 2020 displayed tsantsa (shrunken heads), decorated skulls, and other human remains. In total, Laura and the Pitt Rivers Museum staff removed 123 human remains, or „objects“ containing human remains, such as hair, teeth, skin, bones, and nails, which were on display in various parts of the exhibition. Today these have been replaced by panels that feature information on the coloniality of collections, categorizations, and research practices.

However decolonial this intervention may be, it did not change the way the exhibition space affected us. The so-called objects embodied colonial violence in ways that overshadowed the important transformation undertaken by the team – the removal of human remains in the collection.